'Yes, I'm an Elitist'

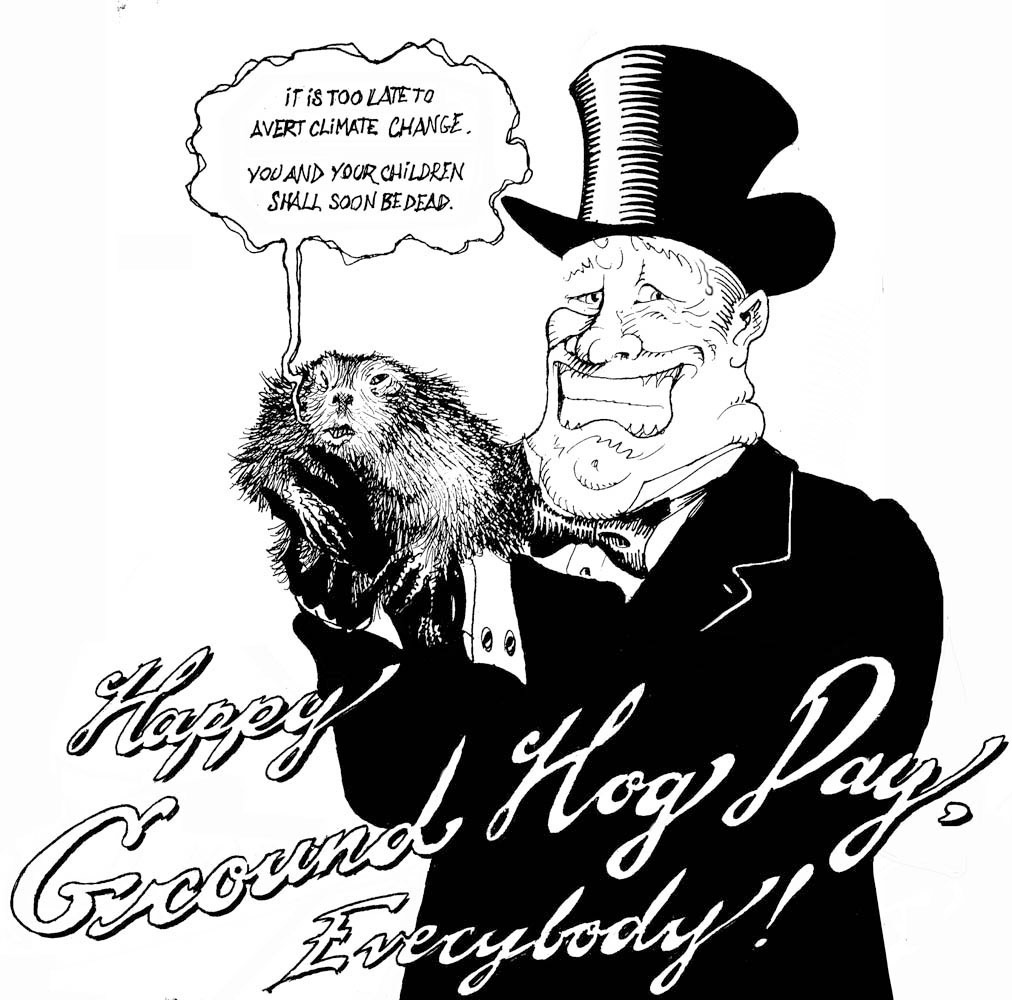

The second part of my conversation with the essayist and cartoonist Tim Kreider.

Welcome back to my conversation with the writer and cartoonist Tim Kreider. It’s a two-parter and this is part two. Here we dig in to Tim’s writing process and the much mythologized writer-editor relationship.

If you’d like to read the first part, in which we discuss the perennial “Why write?” question and other fun stuff about the writing and cartooning vocations and my useful introduction to his work and career, you can find it here. (Y’all make sure to come back here, now!)

Tim’s Substack is called The Loaf, should you care to visit him there at his own house, without my hovering around.

My words are in bold. Tim’s are in Roman, as they say.

OK, go.

~ ~ ~

Can you talk a little bit about how your essays come into being? Your process of thinking about or germinating an idea then recognizing that you are going to stick with it and complete an essay?

TIM: One thing that makes me disdainful of some essayists is that they don’t take their initial ideas far enough; they just follow them straight to the most obvious conclusion and that’s it, they’re done. If I find I can’t think past the premise and take a piece anyplace interesting or unexpected, the essay just atrophies, and eventually dies quietly on my desktop. (I should really accept I’m never going to finish those drafts and mercy-delete them.)

I take this part of the problem—finding something original and universal in whatever subject I’ve chosen—very seriously; I think it’s your responsibility as a writer, in exchange for asking a reader’s time and attention, to give them as much insight as you can squeeze out of the topic; the essay should ultimately be for them, not for you.

What tends to develop an idea, for me, is having conversations with my friends, who are pretty much without exception smarter than me, and also have the advantage of not being me, so they have different perspectives to offer.

When I was stuck on an essay I was writing about a sex worker friend of mine, trying to figure out how to make it more than some “most colorful character I’ve known” sketch, my first book editor, Amber Qureshi, and I finally went to a little dive bar in the town near my cabin in Maryland where we’d holed up to edit, and resolved to drink tequila there until we got to the bottom of it. I can’t actually remember what solution we hit on, but we’re not still drinking tequila, so we must’ve come up with something.

It’s pretty clear that you and I make a good writer-editor team. I hinted at why I think I gravitated toward you and your work. You were doing things with public writing that I believed needed to be done, that there was too little of — actual humor, well-crafted prose, a dash or moral outrage and somewhere underneath it all a spirit of fun.

People in my business talk a lot about what qualities make a “good editor” — for instance, being a “good listener” — but I’m suspicious of those theories, not least of all because it’s rarely the actual good editors who are devising them. I guess I just think good editors are attentive, curious readers who have good taste and go on their instincts. I recently had lunch with a man who is arguably one of the greatest book editors of the past 50 years and when I asked him to explain what he did to become the Absolute Book Wizard he said: “I just take out the boring stuff.” OK, really? Is there more to it than that for you? Do you think there was something about me or the way I approached the work that made it a positive experience for you?

TIM: To the extent I have a literary career at all, it’s due to two people (excepting my own half-assed efforts): you and my agent, The Fabulous Meg Thompson.

But it wasn’t entirely blind coincidence that brought us together; you were then editing the kind of series that would attract writers like me, and I submitted the kind of essay that appeals to you. So it would follow that our literary sensibilities would be congenial. I do not want this to sound like faint praise, but I think a good editorial relationship is kind of like a good relationship of any kind; it feels easy. It’s hard to say what makes it work well because you’re mostly just conscious of bad things that are, for once, not happening.

Anytime you had to cut an essay of mine by one or two hundred words, I could never remember, when I saw the new version, what was missing. (This is probably an exaggeration—I know there were a couple of jokes or epigrams over the years that I loudly lamented or pleaded to keep.) I used to tell people that I’d trust you to edit my work sight unseen, without my getting a final look-over—which, luckily, the Times doesn’t do as a matter of policy, but it’s hard to imagine a higher compliment to an editor.

Thank you! I gratefully accept. I recall you saying something like that in an email and I printed it out and pinned it up behind my desk at work. What about your work with other editors? What were the good and the bad aspects of some of your other collaborations?

TIM: Amber, whom I mentioned above, is a freelance editor when she’s not employed at one publishing house or another and remains my secret editor-for-life. In addition to diligently drinking tequila with me, she once printed out and physically cut up one of my essays and laid its component paragraphs out on the picnic table on my porch and we then stood up on the bench looking down on it while she rearranged them. (This is an exercise I still do with my students.)

I’m loath to badmouth editors with whom I’ve had negative experiences. I don’t like having my words changed without my consent, obviously. It’s kind of a creepy feeling to see things you never said or thought above your byline. (I remember very early on in my career an editor rewriting the intro to a piece I’d done and using the words “much-ballyhooed,” which I still can’t imagine ever coming out of my mouth.)

And I’ve had some editors who just didn’t share my sensibilities at all. In retrospect, their suggestions were reasonable ones—and in fact probably spared me some public shaming—but I think there was a lack of shared sympathies that made their advice hard to hear or take. Maybe they just hadn’t learned the right tone to take with me. I remember an editor who very hesitantly pointed out that some of the language I was using might possibly sound, to some readers, just a tiny little bit elitist. “Yes,” I explained. “I’m an elitist.”

Do you remember a time when you and I really disagreed about something, or that some editing I did made you truly unhappy?

TIM: I actually don’t recall any really serious disputes we’ve had over editing. I think this is probably because I felt you were always on the side of the essay.

But I love showing my students the dialogue we had about the fine distinction between a “Catch-22” and a “Koboyashi Maru”—which I’ll just reiterate for the record are NOT SYNONYMOUS—a back and forth that ran to some several pages when printed out. (For the record, we split the difference and used the former in print, for the old legacy-media readers, and the latter online for the younger televisually literate.) This was a fun disagreement, though I think we both got fairly adamant about it.

My last piece for the Times, “The Unspeakably Sad Reminder of the ‘Other Paris’,” is one I sometimes talk to my students about when we discuss how explicit vs. implicit to be in writing nonfiction. It’s considered kind of clumsy and inartful in literature to just come out and say what you mean, state the theme whereas it’s kind of expected you should do this in most nonfiction—and more or less demanded of you in op-eds for the Times.

What’s his thesis statement? editors want to know. Where’s the argument? (This seems truer at the moment than it has been in years past.) We went back and forth on this one, I recall; you, acting as an intermediary for editorial forces above you and beyond your control, gently advised me to imagine how I might explain the point of the essay to an intelligent and earnest tenth-grader who wanted very much to understand it. In the end we arrived at some more or less acceptable compromise. But then of course some readers interpreted the essay—which was really just a personal meditation on the lovely romantic touristy side of life and its concealed obverse of unglamorous illness, age and decline—as a condemnation of the French health care system. So who’s to say; maybe I shoulda been more heavy-handed.

Can you talk about pieces like “The Busy Trap” or “I Know What You Think of Me” that spawned memes or went viral? Did these events surprise you? What was it like watching your sentences or one-liners spin more or less out of your control?

TIM: I remember being shaken by the reactions to the first couple of essays I wrote for the Times, it being an exponential leap in attention from my cartooning career—and the cartoons also had a self-selected audience of weirdos who were predisposed to like them. I decided, after one or two such experiences, that reading comments online was bad for me. Most people aren’t very attentive readers—a lot of them clearly don’t even read the essays they comment on—and completely fail to get what you were saying, or insist on getting something else that you weren’t saying, or get mad at you for not saying what they want you to have said. Nevertheless, we’re a social species, and you’d have to be a pretty rare specimen not to care at all that lots of strangers are saying mean things about you. Never read the comments became standard advice I would sagely recite to fellow artists, to be interpreted as broadly and metaphorically as possible.

I wrote an essay for Medium about having become a meme with the “mortifying ordeal of being known” line. I don’t at the moment remember what I said in it, but I’d imagine it was that trying to control people’s perceptions of you is a futile and crazy-making game. I’m not egoless—I’d imagine not many artists are—and would obviously like to be better known as a writer, but if I’m going to be eulogized for the Mortifying Ordeal or The Busy Trap or being a die-hard defender of planet Pluto I guess I can’t help it. I’m thinking of Leonard Nimoy’s spiritual journey from writing I Am Not Spock (1975) to writing I Am Spock (1995). This is a journey we all must make.

Are you working on anything now you’d like to talk about? Or are you superstitious about doing that?

I’m right now trying to write an essay about regret for the Times’ series on that subject, which is difficult for two reasons: one is that I seem to suffer even more than most people from that malady, so poking at it is pretty painful. The other is that I don’t have any kind of solution, or even consolation, to offer for the problem of regret. Regrets just sit there like Uranium-238 in my bones, with a half-life of billions of years. Maybe I can offer the reader some commiseration, if nothing else.

I’m supposed to be writing a short book on the future—about how we’re currently at a collective loss for any optimistic vision of a future that anyone other than capitalist assholes and life-hating tech bros actually want. The future is just a little difficult to contemplate without flinching.

I just got a heartening letter from the writer Kim Stanley Robinson, who was very encouraging about the book. He said I was the guy to write it, which may just have been a courtesy on his part, but it feels like a high compliment coming from someone who’s thought more seriously about our future than most people who call themselves “futurists.” So at the moment I’m feeling uncharacteristically motivated and optimistic. Best, probably, to end here, before this ephemeral mood disperses.

Thanks to the journalist Noah Eckstein, who helped with the editing and preparation of this interview.

I love Tim Kreider’s work. Thank you for this window into his process. I especially love his warmth, humor, and deep humanism. Not to mention his fireworks with words. A splendid writer!

Really enjoyed this interview! Thanks for sharing it with the world.